As part of her senior-year study of World War I, Sofia Bongiorni and her classmates visited Memorial Oak Grove this fall. Readers will enjoy and appreciate the perceptive reflections in her essay.

My senior year study of World War I culminated in an hour spent thinking about the meaning of the war as I sat with my sketchbook in a grove of oaks on the campus of Louisiana State University, about three blocks from my school.

The day before I had researched the life of Jasper Joseph Neyland, a soldier from Washington, Louisiana, who died November 10, 1918, the day before the armistice.

The LSU Memorial Grove contains 31 oaks planted in 1926 for students and alumni who died in the war. Thirty trees are labeled for individual soldiers, with one dedicated to the Unknown Soldier buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The afternoon we gathered at the grove, our teacher Mr. Empson gave us these instructions: Find the tree planted for the soldier you researched and have a seat. Then reflect on the war in its entirety. Draw, write a poem or a short story, take a picture; do what makes sense to you, he said.

I found Neyland’s tree, unfolded a stool I’d borrowed from the science classroom and settled into the shade. I did not know where to begin.

My head was full of facts about the war. Our study of it had begun with summer reading of Europe’s Last Summer by David Fromkin, which argues that German generals had been preparing for war with Russia for many years by 1914.

At the start of the school year, we spent a month examining the causes of the war and the events leading up to its outbreak. We proceeded to learn the meaning of terms like “over the top,” “no man’s land” and “trench warfare.” We studied major battles, even looking at pictures of the aftermath of individual skirmishes. We read chapters from Henry Kissinger’s Diplomacy, in which he argues that a “political doomsday machine” guaranteed the world would go to war.

We read a soldier’s first-hand experience of surviving a mustard-gas attack. My class discussed war strategies and the impacts of new weaponry. We looked at pictures of generals, soldiers, weapons, maps, the German Kaiser and the Romanov family of Russia.

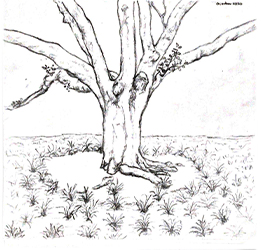

We did not bring books with us to the oak grove. I wasn’t sure how to express the magnitude of what we had studied. I looked around, hoping an idea would come to me. I looked up at Joseph Neyland’s tree. That’s when I knew what I wanted to draw—his tree.

We did not bring books with us to the oak grove. I wasn’t sure how to express the magnitude of what we had studied. I looked around, hoping an idea would come to me. I looked up at Joseph Neyland’s tree. That’s when I knew what I wanted to draw—his tree.

Oak trees are all over Louisiana, but I hardly ever take a moment to really admire them. The enormous branches of Neyland’s tree hung very low in some spots, almost touching the ground. Other branches reached from one tree toward the next, intertwined with vines and supporting Spanish moss and other life, from squirrels to beetles to birds.

I began to think about the war, and how many individuals bravely gave their lives. There are only 31 trees in the memorial, but their branches stretched far and filled the sky with countless leaves. It was windy and humid, hot even in the shade. Looking at all the leaves above, I realized this tree was living to serve and support the lives of others, just as Neyland had done.

Students walked by obliviously, completely unaware of the meaning of these trees. I wondered how many of them knew there was a grove of trees planted for World War I soldiers in the middle of campus, and how young people just like them died in the war.

I thought about what I had learned about Joseph Neyland. The website about the memorial grove included a picture of each soldier honored by a tree with a brief biography about where they grew up and how they died. We could choose the soldier we wanted to study, and Neyland’s wide smile drew me in right away. His hometown of Washington is only about one hour from where I live in Baton Rouge. What struck me most when I read his bio was how much he had been loved. He sent letters home to his girlfriend until he was killed by shrapnel on the front lines in France.

Although Neyland died, his tree and his legacy live on. In history class, a lot of what we studied was about the higher ups—generals, diplomats, leaders—but the war could only be won because of individuals like Neyland who fought bravely and lost their lives.

As I drew, I thought about the war and the ambiguity of its beginnings and the lives lost. I found it overwhelming to look around the grove and see those 31 trees. Thirty-one trees for millions of lives lost. Again I noticed the magnitude of the branches above, which stretched out, almost reaching to the other trees’ branches, unifying the trees. The branches seemed like they were holding each other, supporting each other and bringing each other up.

Planting a tree is an amazing way to remember someone, I thought, and drawing this tree made me feel connected to the war, and to Jasper Neyland, in a way that surprised me. One thing I knew for certain as I sat drawing that tree is that I will never again think of the millions of soldiers who died in the war without thinking of him. That is how I will think about the entirety of the war itself.

This experience was an unforgettable way to conclude our study of World War I. It combined what is important to me as a student by complementing intense study of a subject with the chance to make a personal connection to that subject. I learned so much in Mr. Empson’s class about what historians know about the war, but I also had the chance to form my own opinion about it. It also made me see in a new way how all of us are connected to far away people and events that feel abstract. I often walk or drive with my family by the oak grove at LSU. Now every time I do that, I will think of “my” soldier Jasper Neyland.